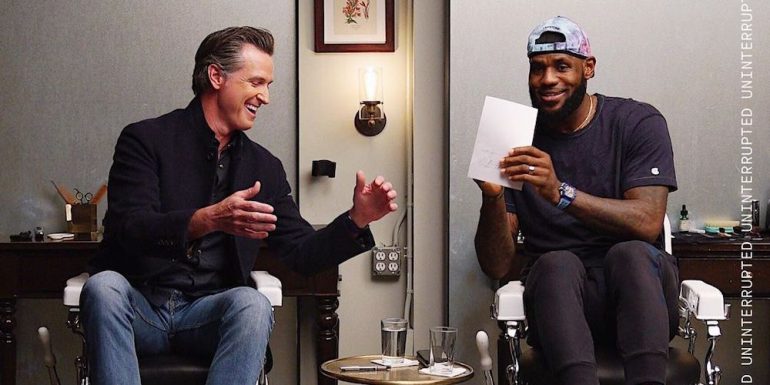

The NCAA’s tyrannical reign of emptying student-athletes pockets with the same vigor Suge Knight displayed while dangling Vanilla Ice upside down over a balcony for the rights to his album royalties, is approaching its denouement. On Monday morning, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed HB 206, named the Fair Pay to Play Act on HBO’s The Shop alongside LeBron James, Maverick Carter and Diana Taurasi. The bill which permits student-athletes to hire agents and monetize their amateur careers through endorsements, sponsorships, apparel deals and other entrepreneurial pursuits, has been controversial since it was introduced by states senators in February. Yet, it passed through the California Senate with a 31-5 vote and flew through 73-0 in the State Assembly.

The bill’s language preventing student-athletes from being penalized by institutions such as the NCAA and member universities for accepting aforementioned compensation once again makes California the center of a contemporary gold rush.

From Silicon Valley to Hollywood, California has always been a trendsetting nation-state. Until recently, the Land of Milk and Honey was the only state able to set its own fuel efficiency rules. Due to its robust economy, car manufacturers were often forced to build and sell vehicles nationally which met California’s high emissions standards or risk being squeezed out of a economy that ranks fifth nationally in gross domestic product.

That’s analogous to what this rule will force the NCAA to do. The Pac-12 will fracture along the San Andreas Fault if California universities secede from the NCAA. The ensuing upheaval occurring in college sports’ Land of Milk and Money will either topple the NCAA or force it to adapt like domestic car manufacturers have.

“This is the beginning of a national movement—one that transcends geographic and partisan lines,” Newsom said on The Shop. “Collegiate student athletes put everything on the line—their physical health, future career prospects and years of their lives to compete. Colleges reap billions from these student athletes’ sacrifices and success but, in the same breath, block them from earning a single dollar. That’s a bankrupt model—one that puts institutions ahead of the students they are supposed to serve. It needs to be disrupted.”

In response, HB 206 has inspired a fresh round of fear mongering from detractors. The “lift yourself up by your own bootstraps” crowd quickly descended to defend the NCAA cartel putting its boot on the necks of student-athletes and chastised Newsom’s Fair Pay to Play Act. Instead of considering the positive ramifications and how it could be beneficial for the lives of student-athletes, the outspoken dissenting crowd has internalized NCAA talking points against pay-for-play while transmitting their own negative narcissistic thoughts about how this will alter their college football viewing experience. They’ve spread false claims about universities having to cut scholarships in non-revenue producing sports in order to play basketball and football players. The NCAA could rule California universities ineligible for postseason competition, but that also seems unlikely.

In reality, California’s law and others like it won’t affect the distribution of scholarships in non-revenue sports like volleyball, baseball or gymnastics. It won’t have any impact on the bottom lines which fund those programs because players won’t be on the university payroll.

HB 206 doesn’t rob from Peter to pay Paul. It finally allows both athletic departments and athletes to tap into their own individual revenue streams. Yes, most Division I student-athletes are taken care of by their athletic departments, but putting a cap on their compensation has always seemed unnecessary.

Even jersey sales constitute less than 5 percent of the income for athletic departments, which is why many Division I programs barely hesitated before phasing out the production of jerseys featuring popular players numbers.

For those genuinely concerned about whether this will have an adverse effect on college sports as a whole, their concerns are unfounded. Tim Tebow, Doug Gottlieb and Darren Rovell have been among the most vocal critics of this bill.

Florida quarterback Tim Tebow is a naive romantic who recently waxed philosophically about an age of innocence during his halcyonic days at the University of Florida during the previous decade when college sports wasn’t rife with corruption and money. Tebow ennobles head coaches, athletic directors, bowl and NCAA execs with the intentions of the charitable missionaries he grew up around when that couldn’t be further from the truth. He also turns a blind eye to how money corrupted his own Florida Gators teammates at the height of his own popularity so we shouldn’t be surprised.

Outback Bowl Numbers.

Players compensation:

$550 each (souvenirs/gift cards)Guy who organizes the bowl:

$1,045,000 https://t.co/9j0AriBocZ— Matt Galambos (@Galambos47) December 26, 2018

Saps like Tebow view the end of amateur football as a binary war between passion versus profit. However, his preachy tone, blind obedience to the NCAA and anti-choice stance on pay-to-play is actually on-brand with his Evangelistic worldview.

There are also the ghouls of Gottlieb’s ilk, who are making bad-faith arguments against college athletes profiting off their own ability and hard work.

1-the unintended consequences are massive & threaten the entire industry 2-creates entitlement for kids 3-makes them professionals which is not nor should it be the intent 4- it is pay for play shielded in a lie of “name and likeness” https://t.co/t54qTyC6f3

— Doug Gottlieb (@GottliebShow) September 30, 2019

Gottlieb’s response is dripping with irony considering he was banished from Notre Dame for committing credit card fraud after his freshman year over two decades ago. It sure seems like he could have benefited from a legal cash flow as an amateur.

If you know a struggling middle class bootlicker who constantly runs to the defense of millionaires or billionaires grousing about their high tax rates, you have an idea of how tone-deaf ex-NCAA athletes and class traitors like Tebow or Gottlieb sound like expressing their opposition to HB 206’s passing. If these are the arguments being made by figures like Gottlieb, then the morality and credibility battle has already been won by players. All that’s left is the legal terrain.

For decades, cheating in the form of improper benefits furtively siphoned to players and their family members in exchange for a specific student-athlete’s commitment to join a program’s recruiting class has been rampant throughout the NCAA’s underbelly. In 2017, the FBI conducted a sweeping sting operation into corruption in college basketball and secured indictments of multiple coaches and an Adidas exec who were involved.

Most of the federal government’s indictments were based on flimsy, money laundering and wire fraud charges. However, if the parents, players, coaches, agents and the Adidas exec outed in Operation Varsity Blues were allowed to deal out in the open, they wouldn’t be forced to resort to illegal methods to compensate athletes.

Ohio State athletic director Gene Smith came out in opposition to HB 206, citing the dark forces its implementation will attract.

“My concern with the California bill — which is all the way wide open with monetizing your name and your likeness — is it moves slightly towards pay-for-play,” Smith said, “and it’s very difficult for us — the practitioners in this space — to figure out how do you regulate it. How do you ensure that the unscrupulous bad actors do not enter that space and ultimately create an unlevel playing field?“

Like Smith, sports business journalist Darren Rovell is also living in a fantasy world in which student-athletes monetizing their own images will attract more illicit money and shady figures to college football than those already infesting its pay-for-play black market.

I’m not arguing for or against college athlete endorsements, but this is what comes with it: 1. The end of the NCAA, 2. Fewer rules, more cheating, 3. Complete professionalization of college sports — players won’t be tied to academics, likely won’t need to go to class.

— Darren Rovell (@darrenrovell) October 1, 2019

What those Armageddon fallacies disregard is that, what were previously improper benefits will no longer be illicit. When marijuana was legalized in the state of Colorado, agent provocateurs and reprobates didn’t flood the state and create chaos, it just turned a lucrative verboten industry into a legitimate commercial enterprise.

Instead of descending into a dystopian hinterland, Colorado became an example to the rest of the nation for the advantages of taking an industry that once operated in the shadows, legalizing and regulating it. Sunlight is the best disinfectant. The NCAA should drop its false piety and take notes.

More than anything, the NCAA is protective of its tax-exempt status. This status exists because NCAA bylaws assert the differences between student-athletes and professionals.

HB 206 walks the line as student-athletes won’t become employees on the university payroll.

There remains a separation of church and state as California universities won’t be inking players to contracts beyond the provisions included in their standard scholarships. They will still be required to maintain a minimum GPA to remain eligible, even if they often aren’t able to attend classes or choose their desired major. Athletic departments will still make money hand over fist through billion-dollar television contracts, apparel deals and off ticket revenues.

Now, California student-athletes can individually cash in as well. Not every college football star has a lucrative pro career over the horizon. Denard Robinson, Pat White, Troy Smith, Johnny Manziel had the brief windows when their marketability was at its zenith, squandered because of the NCAA’s arcane amateurism rules.

Trent Richardson, LaMichael James, Ron Dayne, Toby Gerhart, Noel Devine, Steve Slaton and CJ Spiller never made the same impact in the NFL, but could have padded their savings accounts in college. The NFL’s rookie wage scale contracts can be especially cruel to even the most gifted collegiate running backs who have the shortest athletic primes. There’s no better time to strike on their earning potential than while the iron is still hot.

The NCAA won’t be caught completely flat-footed. It will have until January 1, 2023 to catch up with California. By 2023, the NCAA may finally have been forced to comply with California law instead of vice versa. State legislators in New York, South Carolina and Florida have proposed adopting their own facsimiles of HB 206.

The NCAA has always been sluggish in addressing inequities or faults in their unnecessarily Byzantine bylaws. Their strict definition of amateurism has been getting chipped away at for 100 years, but HB 206 is the most avant-garde quantum leap yet. There was once a time in the embryonic stages of the NCAA when college scholarships were an impermissible benefit for student-athletes.

Colorado Buffaloes receiver/return man extraordinaire Jeremy Bloom and freestyle skier became a cause-célèbre in the early 2000’s after the NCAA refused to grant him a waiver to seek sponsors who could finance his Olympic training. Bloom eventually sacrificed his final two years of eligibility in order to accept sponsors for his training for the 2006 Torin Winter Olympics. In response, the NCAA added exemptions for Olympic athletes who require lucrative sponsorships just to compete.

In 2015, the NCAA added an exception in allowing athletes who compete in individual sports to receive prize money related to their performances in open competitions such as the Olympics. The transfer process has also been relaxed on a number of occasions for grads and those facing hardships leading to the advent of an imperfect, but more modern pseudo-free agency that currently rankles college basketball and football purists.

As this catches steam nationwide, state universities being put at a competitive disadvantage will likely put pressure on local governments to rewrite their own laws until this trend reaches critical mass. Instead of changing for the sake of student-athletes’ well-being, the NCAA will evolve for their own self-preservation because ultimately looking out for self, not the overall well-being of student-athletes, has always been their primary objective.